Peter Chang was the Faberge of the 21st century. His jewellery creations were unorthodox, outlandish, outrageous, extravagant, witty, sexy, and off the wall. Once seen, never forgotten. High voltage colour was his trademark. These objects d'art were large, flamboyant, stylish, post-modern. Meanwhile Chang himself was quiet, always unobtrusive, a hard working, shy genius whose smaller pieces took 400 hours to make.He came be called 'the Scottish jewellery artist' because he lived here for 30 years, but in fact arrived in Glasgow in 1987 when his wife, Barbara Santos-Shaw was appointed head of Printed Textiles at Glasgow School of Art. He met his wife at a party in 1968. They were together nearly 50 years, and married in 1998. It was a very happy and creative partnership, "He was witty, kind, gentle. It was truely wonderful - given a few bickerings!" she says.Already well known, soon his studio workshop in their southside home was a beacon for museum curators and collectors worldwide.His unique visual language came from his imagination. Part Chinese but British born, his oriental ancestry is evident in his innate love of decoration and pattern, and his handling of exuberant colour and exotic shape. Chang trained as both sculptor and printmaker,. After a first degree in Art and Graphic Design at Liverpool 1963-66, he left for Paris to study printmaking at the famous Hayter Printmaking Atelier, followed by a postgraduate in sculpture and printmaking at The Slade, University College, London. It was all a far cry from his modest, even humble beginnings. Only after years working on sculptural projects, interiors and furniture design, did he turn to jewellery in the late 1970s, first making earrings for his wife.As a top rank international artist, Chang's work is in the collection of museums in Germany, Australia, the Netherlands, China, Hawaii, Finland, Switzerland, Italy, in New York's Metropolitan, the Smithsonian, Musee des Arts Decoratifs Montreal, Graves Art Gallery Sheffield, British Council, National Museum of Scotland and numerous private collections, especially in America. He was the winner of many awards: 1989 1st prize Scottish Gold Award, 1991 Merseycraft 1st Prize, 2003 Hoffman Preism Munich, but the one that really put him in the spotlight was the 1995 Jerwood Prize for "lasting significance and daring brilliance."Ironically the day after his death last week art transporters collected work to ship to Rome where his show will open 14th November at the Museo Nazionale delle Arti del XX1 Secolo. Recent exhibitions have been at the Musée d'Art Moderne, Paris and in Germany at the Schmuckmuseum Pforzheim, yet as is the case for so many artists, Glasgow and Edinburgh failed to appreciate his gifts.Mention jewellery, the majority think of gold or diamonds. Chang's raw materials are rather different: commonplace plastic off cuts, worn toothbrushes, old felt-tip pens, broken rulers, razors - anything acrylic. In the 1970s living in his home town of Liverpool, much of it was obtained from shops in Liverpool’s Chinatown. Red and yellow were popular colours in that community, and this colour combination often features in his work. From these unlikely beginnings, as if by magic, he created reptilian bracelets, mosaic broaches, cloisonne earrings and baroque mirrors of exquisite beauty.Chang used plastic because he wanted something that would reflect the age we live in, and additionally was throwaway. Wood or silver impose their own character. Plastic is anonymous and could be moulded, modeled, sculpted into surreal objects of Medici splendor, Tiffany elegance or crazy frivolity. Chang saw himself as primarily a visual artist who sought to create a synthesis between sculpture and wearable jewellery, but fantasy was always important. Star wars with a dash of mythological beast, lizard skin with leopard spots. 'Object-making is a non-verbal attempt at balancing the intellect with the intuitive,' he explained.I watched Chang’s work for 30 years, visited his studio many times and saw his work develop in complexity and sophistication. Recent work demonstrated a shift to more rigorous, minimal forms, with sculpture again coming to the fore.Chang's material may have been modern, his creations avant garde, but his skills were ancient, painstaking and time consuming. Transforming tiny fragments of brightly coloured acrylic into intricate, immaculate curved brooches or bangles, their surfaces reminiscent of amorphous marine life with the odd fin, horn or pompom, is long, hard, and, it transpired, dangerous work.He never used much in the way of machinery, believing he had more control with the hand, using planes, rasps, needle files, sandpaper and polish. However his technique of building up layers of resin and, over the years, before masks were common, breathing in the fumes, did badly damage his lungs, a tragic price for such fabulous work.Like all fine art, Peter Chang's work provokes an intense physical response: a compulsion to touch, a need to smile and wonder. His unique objects also project an unusual wit and humour. "I like to incorporate a bit of fun: spice it up. People take things too seriously" he once told me. So in the end this deep-thinking man, modest, often silent, leaves us with upbeat works of a cheeky joyous optimism that is rare indeed.

Monday, 29 October 2018

PETER CHANG Obit Nov 2017 The Herald

William Hunter: Anatomy of the Modern Museum – Clare Henry

/ Art Categories Art News, Reviews / Art Tags Hunterian Museum, William Hunter / / / / /

Celebrating the tercentenary of Glasgow University Hunterian founder, Dr. William Hunter obviously calls for a significant exhibition. This impressive memorable display, immaculately presented, is organised by the Hunterian Art Gallery in collaboration with Yale’s Centre for British Art where it travels next Spring.

Hunter’s lifelong passion was education, to spread knowledge and make his vast collection

Hunter was a fascinating man & Allan Ramsay’s superb, famous portrait of William Hunter painted in 1765 when he was 47, catches his charisma. Primarily a private record of a lifelong friendship of two Scots, now London based and at the top of their game with flourishing careers and positions at the court of George 3rd, it also marked a key year in Hunter’s eventful life.

Rubens Portrait The Hunterian Museum

He had recently become physician to Queen Charlotte, led a pioneering life in obstetrics or collecting, and was already looking to establish Scotland’s first ever public museum.

Born at Calderwood Farm near Glasgow, Hunter was 7th of 10 children. At 14 he went to Glasgow University to study theology, but after five years decided to become a doctor. It was recorded, “He never married; he had no country house; a fastidious, fine gentleman, he worked till he dropped and he lectured when he was dying.”

Hunter’s lifelong passion was education, to spread knowledge and make his vast collection “useful to the public.” As his teaching and medical practice developed, he extended his collecting beyond anatomical material. By 1765 Hunter was accruing books, manuscripts, paintings, prints, coins, shells, zoological specimens, using them as visual tools for the new biological and chemical sciences.

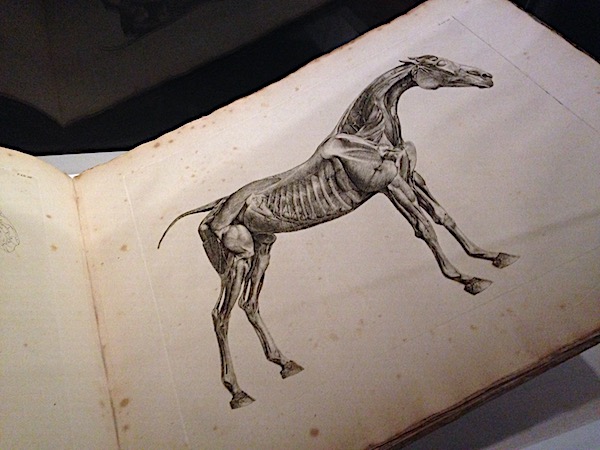

George Stubbs engravings were the first accurate records of equine anatomy Hunterian Museum

He worked with George Stubbs on the first accurate records of equine anatomy, still in use by vets today! With no funds available, over ten years Stubbs engraved and printed the plates himself. The exhibition also contains Stubbs paintings, commissioned by Hunter, including the Nilgai, Moose and Blackbuck.

Initially Hunter hoped he would gain official backing for a national anatomy school in London, but soon learnt that, unlike European centres, state support was not forthcoming. He had to depend entirely on private enterprise throughout his illustrious career. By 1765, this rejection provided the catalyst to go it alone and found his own school and museum.

Happily this coincided with Scotland’s desires. Hunter’s letter from April 1765 notes,”I have a great inclination to do something considerable at Glasgow.”

Private collections were nothing new. Hunter was following a long tradition of providing objects, specimens, for use in the 18th Century’s enlightenment of scientific enquiry, teaching, research and investigation. His 1774 publication, ‘The Anatomy of the Human Uterus’ is world famous. He chose as model for these precise illustrations of dissections Leonardo’s drawings in the Royal Collection, Windsor.

Hunter’s systems of classification, Memory, Reason & Imagination, allow for the “exercise of curiosity across a wide field” – from the fabulous illuminated Hunterian Psalter of 1170, via Chaucer, Pacific hand clubs, Alaskan harpoons, Suriname butterflies, African beetles, Roman gold coins, and glorious oils by Rembrandt, Rubens, Kneller, Zuccarelli, Koninck, Le Nain and Chardin.

Hunter had both connections and cash. He benefited from gifts from his rich clients and friends but he also bought lavishly. From 1765 on his bank accounts reveal significant sums: £50 pounds for the Psalter, £21 for a 1460s block book, spent at home & abroad.

Chardin, ‘Lady Taking Tea’ Hunterian Museum

In 1765, his annus mirabilis, he also bought everyone’s favourite Chardin, ‘Lady Taking Tea’. Ramsay probably encouraged him as both were interested in perception & optics as well as in French painting.

Hunter never travelled, never did a ‘Grand Tour’, so had to rely on others for his collecting.

From the start he was involved with artists, being Royal Academy professor of anatomy. He owned 4000 anatomical drawings of which 500 were commissions.

Hunter was aware of the difficulties of establishing a formal museum. He made 2 wills. His English will bequeathed his museum & library to Glasgow University with specific detailed instructions. The Scottish will provided funds to build the first Hunterian Museum which opened at the Old College in 1807. This was superseded in 1870 when the University moved to the Gilbert Scott building in the city’s West End. In 1980 paintings, sculpture and prints were relocated to the purpose built Hunterian Art Gallery, and the medieval manuscripts to the new University Library. Today there is a threat that this 38 year old building will be destroyed and Hunter’s art thrust into the Kelvin Hall. I sincerely hope this doesn’t happen.

Reuniting, then displaying, objects collected 250 years ago is a difficult task: scores of books propped open, engravings, fossils on pins, inevitably have an academic air. However the show’s imaginative design & useful booklet – plus welcome seats! – helps. Twenty first century museums may have moved on but objects and pictures are still the basis of our visual world, be it via video, 3D printing or plain old drawing.

Clare Henry Oct 2018

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)