RGI

Sept 2019

to come

Clare Henry / Art Journal

Tuesday, 1 October 2019

Monday, 29 October 2018

PETER CHANG Obit Nov 2017 The Herald

Peter Chang was the Faberge of the 21st century. His jewellery creations were unorthodox, outlandish, outrageous, extravagant, witty, sexy, and off the wall. Once seen, never forgotten. High voltage colour was his trademark. These objects d'art were large, flamboyant, stylish, post-modern. Meanwhile Chang himself was quiet, always unobtrusive, a hard working, shy genius whose smaller pieces took 400 hours to make.He came be called 'the Scottish jewellery artist' because he lived here for 30 years, but in fact arrived in Glasgow in 1987 when his wife, Barbara Santos-Shaw was appointed head of Printed Textiles at Glasgow School of Art. He met his wife at a party in 1968. They were together nearly 50 years, and married in 1998. It was a very happy and creative partnership, "He was witty, kind, gentle. It was truely wonderful - given a few bickerings!" she says.Already well known, soon his studio workshop in their southside home was a beacon for museum curators and collectors worldwide.His unique visual language came from his imagination. Part Chinese but British born, his oriental ancestry is evident in his innate love of decoration and pattern, and his handling of exuberant colour and exotic shape. Chang trained as both sculptor and printmaker,. After a first degree in Art and Graphic Design at Liverpool 1963-66, he left for Paris to study printmaking at the famous Hayter Printmaking Atelier, followed by a postgraduate in sculpture and printmaking at The Slade, University College, London. It was all a far cry from his modest, even humble beginnings. Only after years working on sculptural projects, interiors and furniture design, did he turn to jewellery in the late 1970s, first making earrings for his wife.As a top rank international artist, Chang's work is in the collection of museums in Germany, Australia, the Netherlands, China, Hawaii, Finland, Switzerland, Italy, in New York's Metropolitan, the Smithsonian, Musee des Arts Decoratifs Montreal, Graves Art Gallery Sheffield, British Council, National Museum of Scotland and numerous private collections, especially in America. He was the winner of many awards: 1989 1st prize Scottish Gold Award, 1991 Merseycraft 1st Prize, 2003 Hoffman Preism Munich, but the one that really put him in the spotlight was the 1995 Jerwood Prize for "lasting significance and daring brilliance."Ironically the day after his death last week art transporters collected work to ship to Rome where his show will open 14th November at the Museo Nazionale delle Arti del XX1 Secolo. Recent exhibitions have been at the Musée d'Art Moderne, Paris and in Germany at the Schmuckmuseum Pforzheim, yet as is the case for so many artists, Glasgow and Edinburgh failed to appreciate his gifts.Mention jewellery, the majority think of gold or diamonds. Chang's raw materials are rather different: commonplace plastic off cuts, worn toothbrushes, old felt-tip pens, broken rulers, razors - anything acrylic. In the 1970s living in his home town of Liverpool, much of it was obtained from shops in Liverpool’s Chinatown. Red and yellow were popular colours in that community, and this colour combination often features in his work. From these unlikely beginnings, as if by magic, he created reptilian bracelets, mosaic broaches, cloisonne earrings and baroque mirrors of exquisite beauty.Chang used plastic because he wanted something that would reflect the age we live in, and additionally was throwaway. Wood or silver impose their own character. Plastic is anonymous and could be moulded, modeled, sculpted into surreal objects of Medici splendor, Tiffany elegance or crazy frivolity. Chang saw himself as primarily a visual artist who sought to create a synthesis between sculpture and wearable jewellery, but fantasy was always important. Star wars with a dash of mythological beast, lizard skin with leopard spots. 'Object-making is a non-verbal attempt at balancing the intellect with the intuitive,' he explained.I watched Chang’s work for 30 years, visited his studio many times and saw his work develop in complexity and sophistication. Recent work demonstrated a shift to more rigorous, minimal forms, with sculpture again coming to the fore.Chang's material may have been modern, his creations avant garde, but his skills were ancient, painstaking and time consuming. Transforming tiny fragments of brightly coloured acrylic into intricate, immaculate curved brooches or bangles, their surfaces reminiscent of amorphous marine life with the odd fin, horn or pompom, is long, hard, and, it transpired, dangerous work.He never used much in the way of machinery, believing he had more control with the hand, using planes, rasps, needle files, sandpaper and polish. However his technique of building up layers of resin and, over the years, before masks were common, breathing in the fumes, did badly damage his lungs, a tragic price for such fabulous work.Like all fine art, Peter Chang's work provokes an intense physical response: a compulsion to touch, a need to smile and wonder. His unique objects also project an unusual wit and humour. "I like to incorporate a bit of fun: spice it up. People take things too seriously" he once told me. So in the end this deep-thinking man, modest, often silent, leaves us with upbeat works of a cheeky joyous optimism that is rare indeed.

William Hunter: Anatomy of the Modern Museum – Clare Henry

/ Art Categories Art News, Reviews / Art Tags Hunterian Museum, William Hunter / / / / /

Celebrating the tercentenary of Glasgow University Hunterian founder, Dr. William Hunter obviously calls for a significant exhibition. This impressive memorable display, immaculately presented, is organised by the Hunterian Art Gallery in collaboration with Yale’s Centre for British Art where it travels next Spring.

Hunter’s lifelong passion was education, to spread knowledge and make his vast collection

Hunter was a fascinating man & Allan Ramsay’s superb, famous portrait of William Hunter painted in 1765 when he was 47, catches his charisma. Primarily a private record of a lifelong friendship of two Scots, now London based and at the top of their game with flourishing careers and positions at the court of George 3rd, it also marked a key year in Hunter’s eventful life.

Rubens Portrait The Hunterian Museum

He had recently become physician to Queen Charlotte, led a pioneering life in obstetrics or collecting, and was already looking to establish Scotland’s first ever public museum.

Born at Calderwood Farm near Glasgow, Hunter was 7th of 10 children. At 14 he went to Glasgow University to study theology, but after five years decided to become a doctor. It was recorded, “He never married; he had no country house; a fastidious, fine gentleman, he worked till he dropped and he lectured when he was dying.”

Hunter’s lifelong passion was education, to spread knowledge and make his vast collection “useful to the public.” As his teaching and medical practice developed, he extended his collecting beyond anatomical material. By 1765 Hunter was accruing books, manuscripts, paintings, prints, coins, shells, zoological specimens, using them as visual tools for the new biological and chemical sciences.

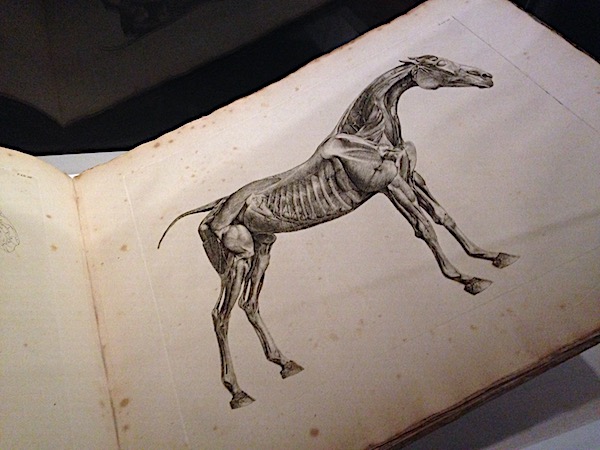

George Stubbs engravings were the first accurate records of equine anatomy Hunterian Museum

He worked with George Stubbs on the first accurate records of equine anatomy, still in use by vets today! With no funds available, over ten years Stubbs engraved and printed the plates himself. The exhibition also contains Stubbs paintings, commissioned by Hunter, including the Nilgai, Moose and Blackbuck.

Initially Hunter hoped he would gain official backing for a national anatomy school in London, but soon learnt that, unlike European centres, state support was not forthcoming. He had to depend entirely on private enterprise throughout his illustrious career. By 1765, this rejection provided the catalyst to go it alone and found his own school and museum.

Happily this coincided with Scotland’s desires. Hunter’s letter from April 1765 notes,”I have a great inclination to do something considerable at Glasgow.”

Private collections were nothing new. Hunter was following a long tradition of providing objects, specimens, for use in the 18th Century’s enlightenment of scientific enquiry, teaching, research and investigation. His 1774 publication, ‘The Anatomy of the Human Uterus’ is world famous. He chose as model for these precise illustrations of dissections Leonardo’s drawings in the Royal Collection, Windsor.

Hunter’s systems of classification, Memory, Reason & Imagination, allow for the “exercise of curiosity across a wide field” – from the fabulous illuminated Hunterian Psalter of 1170, via Chaucer, Pacific hand clubs, Alaskan harpoons, Suriname butterflies, African beetles, Roman gold coins, and glorious oils by Rembrandt, Rubens, Kneller, Zuccarelli, Koninck, Le Nain and Chardin.

Hunter had both connections and cash. He benefited from gifts from his rich clients and friends but he also bought lavishly. From 1765 on his bank accounts reveal significant sums: £50 pounds for the Psalter, £21 for a 1460s block book, spent at home & abroad.

Chardin, ‘Lady Taking Tea’ Hunterian Museum

In 1765, his annus mirabilis, he also bought everyone’s favourite Chardin, ‘Lady Taking Tea’. Ramsay probably encouraged him as both were interested in perception & optics as well as in French painting.

Hunter never travelled, never did a ‘Grand Tour’, so had to rely on others for his collecting.

From the start he was involved with artists, being Royal Academy professor of anatomy. He owned 4000 anatomical drawings of which 500 were commissions.

Hunter was aware of the difficulties of establishing a formal museum. He made 2 wills. His English will bequeathed his museum & library to Glasgow University with specific detailed instructions. The Scottish will provided funds to build the first Hunterian Museum which opened at the Old College in 1807. This was superseded in 1870 when the University moved to the Gilbert Scott building in the city’s West End. In 1980 paintings, sculpture and prints were relocated to the purpose built Hunterian Art Gallery, and the medieval manuscripts to the new University Library. Today there is a threat that this 38 year old building will be destroyed and Hunter’s art thrust into the Kelvin Hall. I sincerely hope this doesn’t happen.

Reuniting, then displaying, objects collected 250 years ago is a difficult task: scores of books propped open, engravings, fossils on pins, inevitably have an academic air. However the show’s imaginative design & useful booklet – plus welcome seats! – helps. Twenty first century museums may have moved on but objects and pictures are still the basis of our visual world, be it via video, 3D printing or plain old drawing.

Clare Henry Oct 2018

Monday, 21 May 2018

PHOEBE COPE, Biggar & Upper Clydesdale Museum, till May 31st.

The art world is a complex place, but always invigorating. I am lucky to see art worldwide. One day mega Kiefer at the crowded Rockefeller Centre Manhattan,

next minute Phoebe Cope's paintings of her life around Coulter Fell, an isolated, exposed but shapely part of a rolling range of high hills of the Scottish Uplands.

which has become over the past decades more denuded of its heather and any shrubby trees, as there have been an increasing number of sheep put on the hills.

Yet, loving 'copious colour,' her hills are alive. I particularly admired 'Book Press, Black Hill & Coulter Fell' seen from her window. Never has the Hill been less black! As she says, "It's interesting to see the shapes of the hills with some of their iron age forts and cultivation terraces, so tightly grazed by sheep, and poc marked by rabbit warrens,"

A lively life informs all her work, creative mark making at its best. It beautifully captures their garden, sycamore in snow, sheets drying, sunflowers, oystercatchers, even scaffolding. She aims for honesty before prettiness, truth before the picturesque.

next minute Phoebe Cope's paintings of her life around Coulter Fell, an isolated, exposed but shapely part of a rolling range of high hills of the Scottish Uplands.

Kiefer symbol in lead takes an overall world view, his huge, dominating awe-inspiring, fearsome book, stick and snake, proving fearsome to many, (but to me reminiscent of the powerful doctor's symbol of medicine, stick & snake.)

In the lovely gallery space at the new(ish) Upper Clydesdale Museum in Biggar Cope relies on a close, personal but recognizably fundamental view of life, familiar to us all.

In Cope's pictures all humanity is there - the cycle of life with raw nature,

babies, animals, farming in all weathers, the seasons with winter chill and lush summer blooms,

intense purple heather one year never to be again, last years brittle discarded Xmas tree put out to rot, toys scattered on the floor. Details of a life well lived and even better observed.

Cope says she relies on instinct. As the daughter of a vigorous painter she is well schooled, as a mother she knows the reality of children which is reflected in her impressive self portrait

which has become over the past decades more denuded of its heather and any shrubby trees, as there have been an increasing number of sheep put on the hills.

A lively life informs all her work, creative mark making at its best. It beautifully captures their garden, sycamore in snow, sheets drying, sunflowers, oystercatchers, even scaffolding. She aims for honesty before prettiness, truth before the picturesque.

Cope's work has a generosity of spirit that is endearing. I warmly advise u to see this show if you can. Good painting is rare to find these days. She is hugely professional - and her work has won prizes and been exhibited with the Royal Academy, Royal Hibernian Academy, Royal Scottish Academy, Royal Society of Portrait Painters, the Gordon W Smith Exhibition, the Machin Art Foundation, Cill Rialaig Project, the Moritz-Heyman Pignano Award, Ruth Borchard Exhibition at Piano Nobile, the Lynn Painter Stainers, the Campaign for Drawing & the Oireachtas.

Her work is represented in the collections of Office of Public Works, the Bank of Ireland, the Blackrock Clinic, HRH the Prince of Wales, as well as numerous private collections.

Her work is represented in the collections of Office of Public Works, the Bank of Ireland, the Blackrock Clinic, HRH the Prince of Wales, as well as numerous private collections.

Sunday, 4 February 2018

GLASGOW GROUP at 60; AGES of WONDER from the RSA, The Maclaurin Gallery, AYR

The Glasgow Group is arguably the oldest artists co-operative going. Now celebrating its 60th B-day, it was established in 1958 by 3 GSA students, Jim Spence, Anda Paterson & James Morrison, who invited 10 others to join them.

Anda Paterson is exhibiting here with her signature Mediterranean peasants. Sadly the beloved Jim Spence, who worked 33 years as GG president, died last year & is much missed.

The GG has held annual shows, & frequently more often, all over Scotland, England, Wales, Norway & Spain, and for over 30 years filled the then splendid McLellan Gallery with their work.

The GG were also invited to provide the huge, exciting inaugural opening show for Tramway back in 1989, (see my Herald review with a pix of Jim Spence) when Douglas Gordon and Rosemary Beaton were invited as 2 young folk, and George Wyllie installed his entire life sized Paper Boat !!

Members have included Bet Low, Philip Reeves, Dawson Murray, Jack Knox, Willie Rodger and many more.

Today the painter Shona Dougall chairs the group which is exhibiting about 100 works in 2 galleries at the Maclaurin Art Gallery in Ayr to celebrate its 60th anniversary.

Artist members now include sculptor Tom Allan, painters Claire Paterson and Susan Kennedy and printmaker Damian Henry.

Artist members now include sculptor Tom Allan, painters Claire Paterson and Susan Kennedy and printmaker Damian Henry.

"When the Glasgow Group first met in 1957 Scottish art was in a bad way," remembers Alasdair Gray of New Lanark fame. He was there so he should know! Back then the GG had an average age of 22. It went on to become a cutting-edge affair, with folk like Sandy Moffat, John Bellany, Richard Demarco et al included. Long before Transmission and current societies, GG has always been a true cooperative.

To keep anything running for 60 years takes time & effort. Current chairman Shona Dougall does a great job, organising - while also painting. I enjoyed her colourful sunlit Still Lifes.

I have been writing about the Glasgow Group for 39 years! I was asked to open their 1989 Tramway inauguration and so was happy to do the same for their 60th b-day exhibition at the Maclaurin Gallery, Ayr

where the work looks very good filling 2 long galleries with vivid, colourful paintings, photographs & prints.

where the work looks very good filling 2 long galleries with vivid, colourful paintings, photographs & prints.

It's an enjoyable array with CLAIRE PATERSON's figure paintings a standout contribution. Great to see her good drawings here.

There is today so much plastic & cardboard installation, sound & 'immersive' - how I hate that word! - stuff, you all know what I mean, that it is a relief to see some fine draughtsmanship & skilled painting. She too studied at GSA as did most others.

There is today so much plastic & cardboard installation, sound & 'immersive' - how I hate that word! - stuff, you all know what I mean, that it is a relief to see some fine draughtsmanship & skilled painting. She too studied at GSA as did most others.

There is an impressive stormy seascape from Gregor Smith

from Will McLean,

Ian Hamilton Finlay,

Stuart Duffin,

Elspeth Lamb,

Beth Fisher -

and Philip Reeves, who was a GG member for many years!!

and wooded landscapes by Susan Kennedy

Prints by Damian Henry include his signature animals

& Claire Paterson's oils complete the picture.

Across the courtyard the RSA's loan exhibition AGES OF WONDER contains some STUNNING prints from Will McLean,

Ian Hamilton Finlay,

Stuart Duffin,

Elspeth Lamb,

Beth Fisher -

and Philip Reeves, who was a GG member for many years!!

Master printmaker IAN MCNICOL who lives in Ayr, will be doing print demonstrations & workshops at the Maclaurin. So make sure to go!

Clare Henry

Thursday, 1 February 2018

STEVEN CAMPBELL, LOVE Tramway Glasgow 2018

Steven Campbell: Large-Scale Collage Work Rich In Formal Invention – by Clare Henry in ARTLYST January 2018

When Steven Campbell arrived at Glasgow School of Art in 1978 age 25, he was a man in a hurry, fiercely ambitious and with enormous energy. Eight years later having conquered the New York art world, he returned to Scotland with his family to continue his assault on contemporary art, producing now famous monumental canvasses teeming with fantastical narratives, vivid in imagery, complex in detail and rich in formal invention.

A flamboyant, charismatic if difficult, prickly figure – CH

Campbell was known for producing paintings at terrific speed, yet between 1988-91 he created a series of 12 large-scale, experimental and complex collages, painstakingly and laboriously made, in an obsessive, even compulsive and time-consuming manner. Only shown once, in 1993, they fill Glasgow’s Tramway gallery till March 25th.

The string, (regular, ordinary cheap white household string, Campbell always kept costs to a minimum,) had first to be painted in multiple shades and tones, then hung out to dry before being cut in 5 or 7 inch lengths, and aligned, thread by thread, side by side, length by length, then stuck individually on the picture. Areas of paper were also textured or patterned by printing from scrap corrugated cardboard or stamps of curled string.

While this obsessive homemade technique would, for the vast majority, limit things to stilted, sterile, tight compositions, Campbell with his genius for compositional fluency, made exciting, dense, free-flowing but never restrained landscape-tableaux of metaphysical territories, or ambiguous, bizarre mise-en-scenes.

While this obsessive homemade technique would, for the vast majority, limit things to stilted, sterile, tight compositions, Campbell with his genius for compositional fluency, made exciting, dense, free-flowing but never restrained landscape-tableaux of metaphysical territories, or ambiguous, bizarre mise-en-scenes.How – and why- did he set himself such an arduous task? Carol Campbell explains it with reference to prisoners of war who created masterpieces out of matchsticks. “A repetitive, exacting, all-consuming process can be therapeutic. I think at that time Steven needed a focus, a change of pace, and he found this contemplative, reflective practice allowed for a healing process for body and mind.”

Usually, Campbell worked in a barn at their remote house in the Fintry hills. It was messy, cold, dark, draughty. But the string needed to dry, and the glue needed heat to work effectively, so he made these works on the kitchen table or floor amid the flow of domestic life. “I could get quite annoyed,” Carol Campbell remembers. “Move all this stuff, I need to get dinner!”

As Sandy Moffat his tutor has commented, “Campbell’s paintings were spaces or theatres of the mind where the viewer would meet and experience bizarre utopias and dystopias, and which created the feeling that the artist’s own life and personality were only screened from us by the thinnest of veils.”

Two cousins with the same Mother ....1991

Campbell was not just well read, he devoured books, skimming through to extract just enough to feed his over-active, fertile imagination so that in these collage pictures myth merges with masque or pose to create illogical charades with a singular sense of urgency.

Campbell’s titles are often as disquieting and confusing as his pictures. Portrait of Two Cousins with the Same Mother who Left them Alone when she was Seventeen, from 1991, includes a large butterfly with a reclining nude to each wing, while below the path to a fairytale cottage comes under sharp-looking shears or scissors. There is obviously no return. Love – which gives the title to the show, also features a central nude plus blue butterfly wings, one hiding Campbell’s trademark hunter with gun – who reappears the most powerful image here: Dream of the Hunter’s Muse, 1991.

Campbell’s titles are often as disquieting and confusing as his pictures. Portrait of Two Cousins with the Same Mother who Left them Alone when she was Seventeen, from 1991, includes a large butterfly with a reclining nude to each wing, while below the path to a fairytale cottage comes under sharp-looking shears or scissors. There is obviously no return. Love – which gives the title to the show, also features a central nude plus blue butterfly wings, one hiding Campbell’s trademark hunter with gun – who reappears the most powerful image here: Dream of the Hunter’s Muse, 1991.This complex interweaving of doe-eyed but very dead deer and a beautiful nude woman fallen in a pool of her own blood while a kitten plays in it, and the impassive hunter looks on, is quite chilling. Despite the beautifully delineated surrounding animals and birds: badger grouse, playful rabbits and pheasant, it sings a sad song of female sacrifice and male indifference.

The Family of the Accidental Angel is another angst-ridden group where the father struggles with heavy rope while his baby lies face down on a bed of actual feathers. Did the angel’s all-seeing green eyewitness and save the child’s fall? Or did she cause it?

I Dreamt I shot Mussolini at Cowes Week, with its floundering, gaily tipping yachts and drowning waving hands, includes Campbell’s favourite murder scenario. Happily, Thoughts of a Vegetarian 1989 is more upbeat and shows Campbell’s beloved Italian sunlit landscape.

Each picture rewards careful scrutiny, sometimes, as here, with serious questions, other times with wit or whimsy, The results are impressive, memorable. Campbell died 11 years ago, but his work continues to enthral.

LOVE, Collages by Steven Campbell, Tramway, Glasgow till March 25th

Words: CLARE HENRY

Photos: Courtesy Marlborough London © Artlyst 2018

Photos: Courtesy Marlborough London © Artlyst 2018

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)